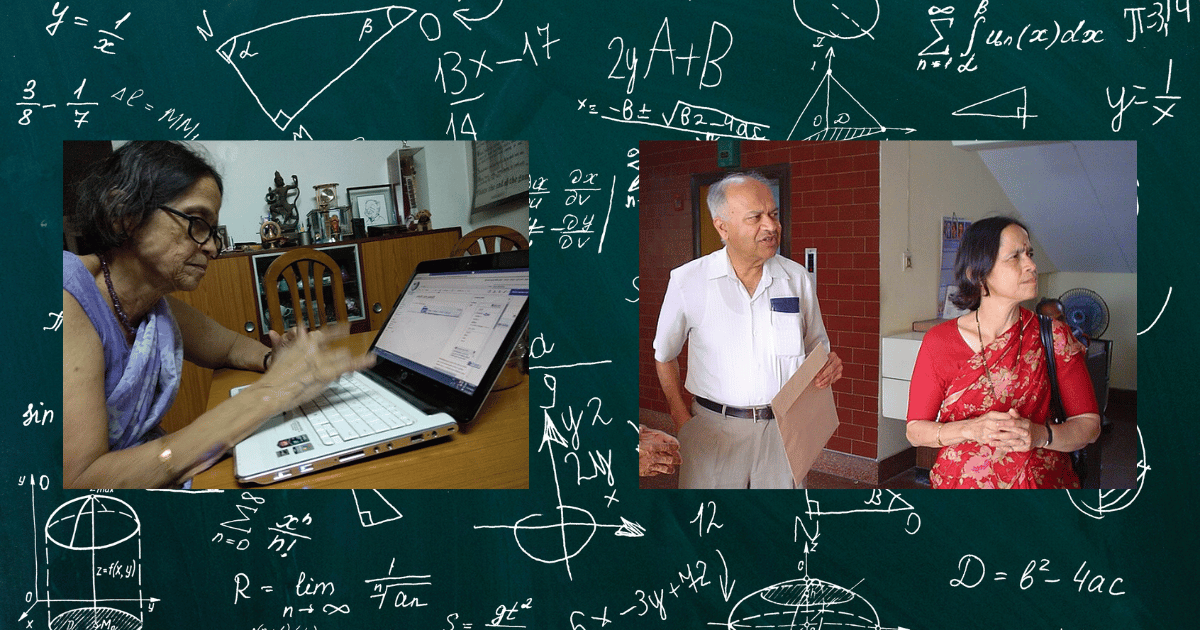

Discover the remarkable journey of Dr. Mangala Narlikar, a pioneering mathematician who balanced family, ambition, and the pursuit of science.

This story captures the life of Dr. Mangala Narlikar, who redefined what it means to be a mathematician in India. Her journey from topping classes in Bombay to changing how math is taught across Maharashtra, while raising a family and battling stereotypes, shows that determination can quietly break barriers. This piece will resonate with students and early-career readers navigating their own paths.

Bombay, 1960s.

Mangala Rajwade never skipped the bus, or returned home late. But every report card, every exam result, made the city pause and look up. The headmaster would smile—“Once again, Miss Rajwade, first in class.” Gold medals collected like stray coins at the bottom of her bag. Even mathematics, that fickle sovereign, bowed in her presence.

And yet, as sunlight filtered through blue monsoon glass, Mangala would fidget on the classroom bench. “You lack ambition,” one teacher murmured after school, eyeing her shuffling feet. The words clung like dust to her sari. She believed them a little.

She did not storm into rooms. She waited—politely, softly—at the threshold. But once through, she rewrote the rules, quietly, from the inside.

Her mother’s friends would whisper, “Girls and numbers don’t mix.” Mangala would smile and keep solving, each equation a gentle rebellion. When Bombay University announced exam results, Mangala’s name danced at the top.

But brilliance never had free rein—especially for women.

The city’s air, thick with the scent of jasmine and petrol, carried rumors: “Girls mustn’t study long. Marriage is coming.”

Marriage did come. Jayant Narlikar—already a star, drifting between Cambridge and cosmic conferences. He was proud of her, encouraged her math. Yet in their small kitchen in Cambridge, Mangala’s world bent to tea, chapatis, and the whir of a washing machine.

She taught undergrads in England, making algebra gentle for young minds far from home. But with every suitcase packed for another move, every sari folded for a new season, her research slipped out of reach.

Men asked, “So, do you still do any mathematics?” She smiled, deflecting, “I teach. I enjoy it.”

“I was setting up a home. Cooking. Entertaining. Making sure the children wore matching socks,” she recounted later, her laugh half-amused, half-wistful.

Three daughters were born. She sewed school uniforms, explained fractions at the dinner table, and eased her in-laws through Bombay’s fierce monsoons.

Then, Bombay again. The 1970s.

A government housing assignment near the Tata Institute of Fundamental Research changed everything. No hours lost on buses. Just a short walk—a second chance, quiet and unannounced.

Children slept. In-laws rested. In the hush of early morning, Mangala cracked open thick journals and battered notebooks. Her ambition, never dead, flickered awake.

At thirty-eight, she enrolled for a PhD—analytic number theory, her joy from long ago. She attended lectures, battled self-doubt, and published proofs that brought pride and order to the mathematics of prime numbers and complicated zeta functions.

She never became a “full-time scientist”—there wasn’t time. But she became something rarer—a steadfast, part-time revolutionary.

Her greatest theorems walked in cotton skirts and called her “Mummy.”

Geeta, Girija, Leelavati—each raised to believe brilliance belonged to anyone willing to work, regardless of gender. They grew up watching their mother patch holes in socks while dashing off mathematical notes for submission to foreign journals.

But it was the classrooms of Maharashtra that held Mangala’s legacy.

As head of Balbharati, she declared war on rote learning.

“Let’s make mathematics less frightening,” she urged.

Let children discover patterns, not just memorize tables.

She authored stories where little girls outwitted market vendors using ratios, and boys solved riddles with decimals. She simplified Marathi number-names—so every child could count with confidence. She made sure textbooks cost no more than a cup of tea.

Girls wrote her notes: “Madam, now I want to become a mathematician too.”

Then cancer knocked—quiet, inexorable.

Mangala did not rage or pray.

She simply said, “I believe in science.”

She trusted the doctors, measured her medication as she had always measured everything: carefully, precisely.

One evening, as the sun slipped over the Arabian Sea, a friend asked her, “How did you do it, Mangala? How did you last, when the world expected you to stop?”

Mangala smiled, dusted chalk from her hands, and whispered,

“I never stopped, not really. Just… took quieter roads.”

So next time someone wonders, “Where are the Indian women in mathematics?”—

just remember Mangala, threading prime gaps between chopping onions, reworking zeta functions between sewing school dresses, whispering new ways to teach between boiling chai.

She was there, always.

Not just proving new theorems—

but proving, again and again, that ambition need not apologize.

Her name was Dr. Mangala Narlikar.

Her equations didn’t only change numbers—they changed what was imaginable.